What is Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs?

Myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs is an acquired, inherited condition that accounts for approximately 80% of all diagnosed canine heart conditions. This prevalent disease affects an estimated 30-50% of small-breed dogs 10 years of age and older. Mitral Valve Disease most commonly occurs in older dogs, but some breeds like Cavalier King Charles Spaniels have a greater predisposition at a younger age.

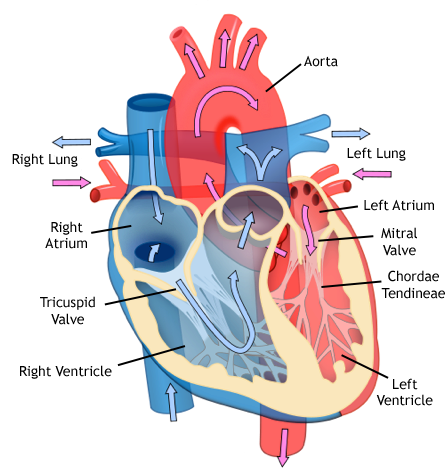

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) affects the mitral valve leaflet, a flap that is located on the left side of the heart, between the atrium and the ventricle. The valve’s tissue tends to degenerate over time, gradually thickens, losing its elasticity and is no longer able to function properly. This lack of a proper closure leads to abnormal reversal of blood flow inside the heart, known as mitral regurgitation. MMVD is the leading cause of congestive heart failure in dogs.

Myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs is usually a gradually progressive disease, meaning that little by little over several years, the valve thickens and leaks more. Gradually, the heart enlarges and pressure can rise. High pressure within the heart leads to congestion in the lungs and fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) in approximately 20% of affected dogs. Rarely, a chordae tendineae (cord), connecting the valve to the left ventricle, may rupture. This complication can lead to sudden pulmonary edema (a buildup of fluid in the lungs making it difficult to breathe).

Diagnosing Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs

The disease is typically first detected by a veterinarian during a routine checkup. A veterinarian or veterinary specialist will usually detect what’s called a heart murmur while listening to your dog’s heart with a stethoscope. A heart murmur is caused by the turbulent blood flow in the heart that creates extra “whooshing” sound.

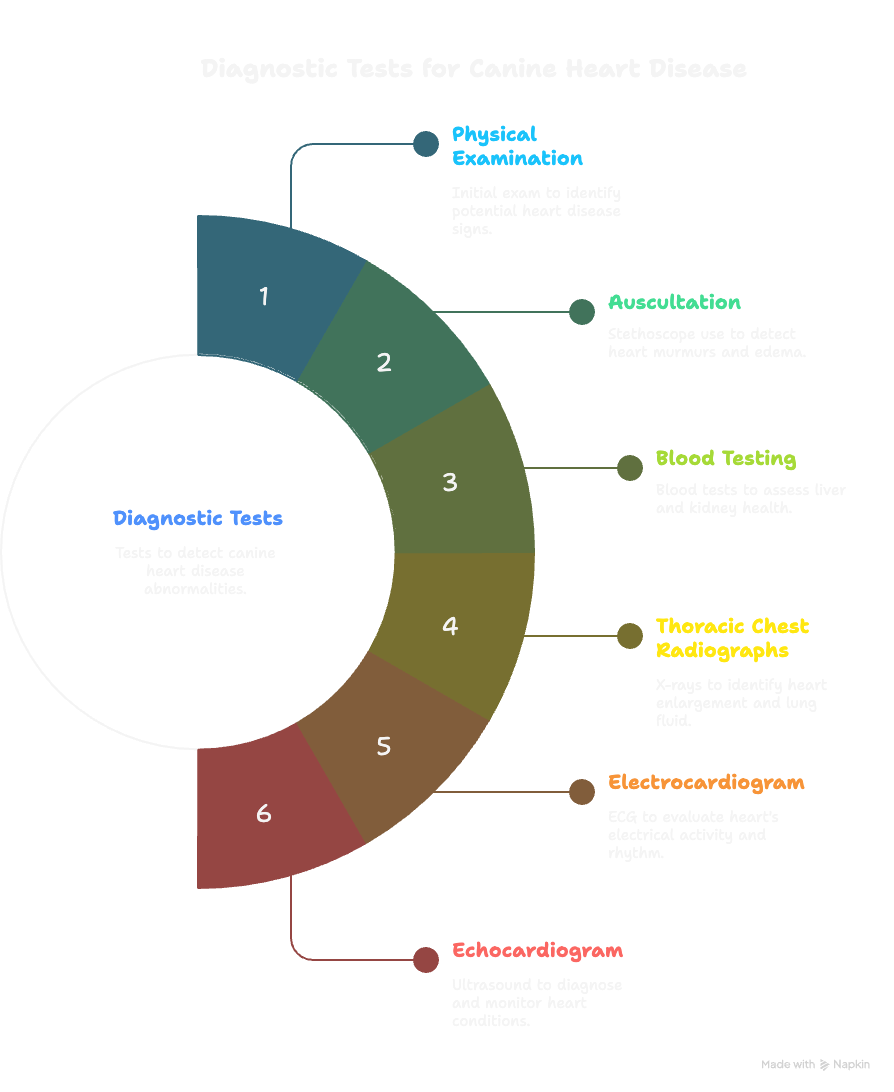

Here is a breakdown of the tests your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist may perform to evaluate for MVD in dogs:

Physical Examination – A veterinary physical exam will be the first test performed by your dog’s veterinarian to determine abnormalities that may indicate a sign of heart disease or other illnesses.

Auscultation – Using a stethoscope, a veterinarian may detect a heart murmur, which is one of the the first signs of canine heart disease. Auscultation tests will also help detect pulmonary edema or fluid build up in the lungs.

Blood Testing – Blood test including a renal panel may be performed to help determine additional abnormalities that may include liver and kidney issues.

Thoracic Chest Radiographs (X-Ray) – If a murmur is detected, your dog may require additional screening. Thoracic x-rays will help determine if there is heart enlargement and can identify fluid build up in the lungs.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) – An ECG may be performed by your veterinary cardiologist to evaluate for electrical abnormalities that can occur in dogs with MVD. An electrocardiogram of your dog’s heart will help determine the extent of your dog’s heart condition and guide your dog’s veterinary cardiologist with determining the best treatment options. Abnormalities in heart rate and rhythm may indicate additional issues like arrhythmias or dysrhythmias.

Echocardiogram (Ultrasound) – An echocardiogram for dogs, often referred to as an echo, is a non-invasive diagnostic test that uses ultrasound waves to create detailed images of a dog’s heart. This test is the key tool in veterinary cardiology for diagnosing and monitoring heart conditions including mitral valve disease. This includes identifying heart function, blood flow, and any regurgitation or leakage that may be present. An echocardiogram is considered a gold standard in cardiac pet health.

Degenerative mitral valve disease may appear as early as 1-5 years of age although commonly detected around 10-11. More than 80% of small dogs under 15 pounds or under are diagnosed as having mitral valve disease in their lifetime. The disease is most common on the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and the Dachshund breeds. Other breeds we see commonly affected include Miniature poodles, Shih Tzus, Maltese, Chihuahuas, Cocker Spaniels, Miniature Schnauzers, Whippets, and Pomeranians.

This disease can also be seen in some larger breeds and mixed breed dogs, although it is less common. Some medium and large breeds are predisposed to heart disease, although not by an anomaly of the mitral valve, usually to cardiac muscle disease known as cardiomyopathy. This accounts for 15-20% of medium and large breed dog’s heart disease.

MVD in dogs is a very common genetic cardiac disease. It is also commonly observed that males are more frequently and more severely affected than females. The disease is progressive, gradually worsening over time, more or less rapidly depending on the individual. The tricuspid valve is also affected in ⅓ of cases. Medications are typically prescribed to relieve the work of the heart and to help resolve pulmonary edema. Medications can, in some instances, be prescribed before symptoms of heart disease develop in order to postpone signs of disease.

Today, however, there are no curative or preventative treatments for this condition. Treatment should always be adjusted on a case-by-case basis through a combination of close communication with your primary care veterinarian, collaboration with board certified veterinary cardiologist, and appropriate, timely diagnostics.

Treatment for Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs

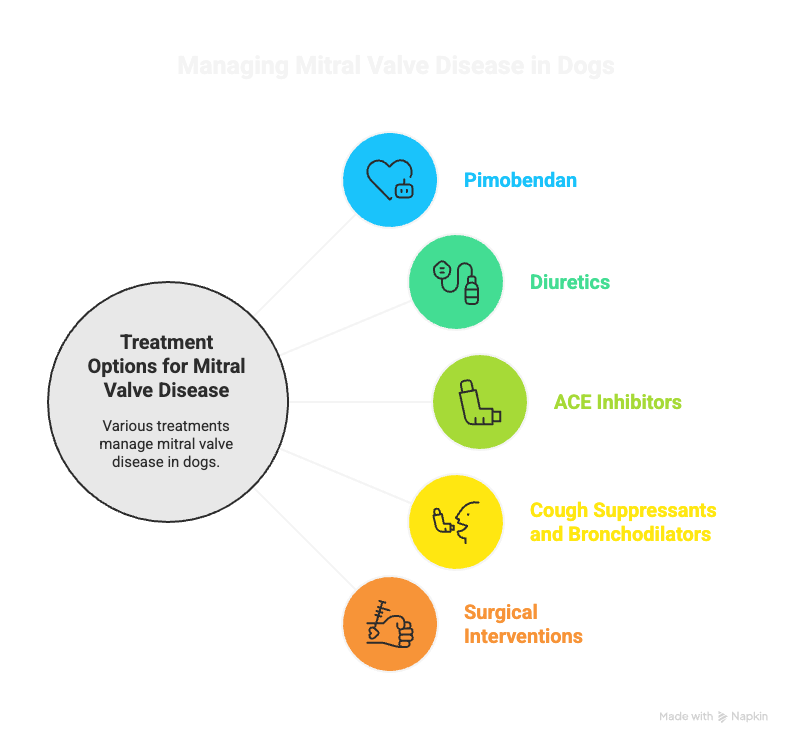

Myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs is a serious heart condition, but with the proper treatment and therapy, the disease can be well managed. Depending on disease progression, various treatment options are available. These drugs are commonly used when the disease progresses to heart failure (Stage C):

Pimobendan (Vetmedin) – Increases the heart’s contractility (positive inotrope) and dilates blood vessels, reducing the workload on the heart.

Diuretics – Furosemide (Lasix) – Removes excess fluid buildup in the lungs (pulmonary edema), alleviating symptoms like coughing and difficulty breathing.

Spironolactone – A potassium-sparing diuretic that helps manage fluid retention while reducing scarring in the heart tissue.

ACE Inhibitors – Enalapril or Benazepril – These drugs relax blood vessels, lowering blood pressure and reduce strain on the heart. These therapies also reduce the degree of water retention by the body.

Cough Suppressants and Bronchodilators – Used in dogs with a persistent cough not directly related to pulmonary edema, to improve breathing comfort. These may also be prescribed due to collapsed bronchi caused by heart enlargement.

Surgical Interventions – Two surgical options exist to reduce mitral regurgitation including TEER – Transcatheter Edge to Edge Repair surgery and the traditional Mitral Valve Repair open heart surgery.

Consequences and Symptoms of Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs

At the onset of the disease, the heart performs physiological adaptation work called the compensatory phase, the disease at this stage is considered “occult”. When the adaptive capacities of the heart are exceeded, symptoms such as fatigue, cough, and fainting, (syncope) may begin to develop in the affected dog.

When these symptoms are present, the disease is now in its “decompensated phase”. Medicines are essential at this point and are typically prescribed for life unless mitral valve repair surgery is decided.

Eighty five percent of dogs that had repair surgery have come off most if not all medications for extended periods of time or life. As this is a continuing progressive disease, the disease continues to advance even after surgery. Every progression is different with each case. Surgery has given a beautiful gift of time for all affected by this terrible disease.

Mitral valve disease in dogs progresses over time, with symptoms varying depending on the disease stage and progression. Recognizing signs early can help manage the condition and delay the onset of congestive heart failure (CHF). Below are the common signs and symptoms:

Early Stages (Stage B1 and B2)

In the early stages, many dogs show no noticeable symptoms. However, veterinary exams may reveal complications like a heart murmur or mild lethargy where the affected dog is more tired and shows exercise intolerance. Coughing caused by the heart enlargement compressing the airways in the chest can also occur.

Progressive Symptoms (Stage C – Clinical Signs of Heart Failure)

As the condition worsens and the heart’s ability to function declines, symptoms become more apparent and will require ongoing treatment to manage symptoms and complications.

This includes shortness of breath or labored breathing due to fluid build up in the lungs, also known as pulmonary edema. Coughing will commonly worsen, often more apparent at night or during exercise.

Reduced stamina and inability to engage in normal activities may worsen as the disease progresses, where your dog may become more tired and lethargic during walks or regular play sessions.

In more advanced stages of heart failure, fainting or collapse may occur, also known as Syncope. This happens due to reduced blood flow to the brain, often triggered by excitement or even at rest(especially in compromised dogs).

Advanced Symptoms (Stage D – Refractory Heart Failure)

In severe cases, dogs may show signs of end-stage heart failure which includes severe fluid retention in the lungs, abdomen or other parts of the body when right side heart failure (tricuspid valve disease) is present.

Symptoms may include a swollen belly (called ascites) from fluid build up in the abdomen, cyanosis or bluish tongue and gums, and a poor appetite.

Open mouth breathing with distress is also a sign of difficulty breathing and respiratory failure that may require immediate care. In advanced stages, mitral valve disease will lead to chronic heart failure and death.

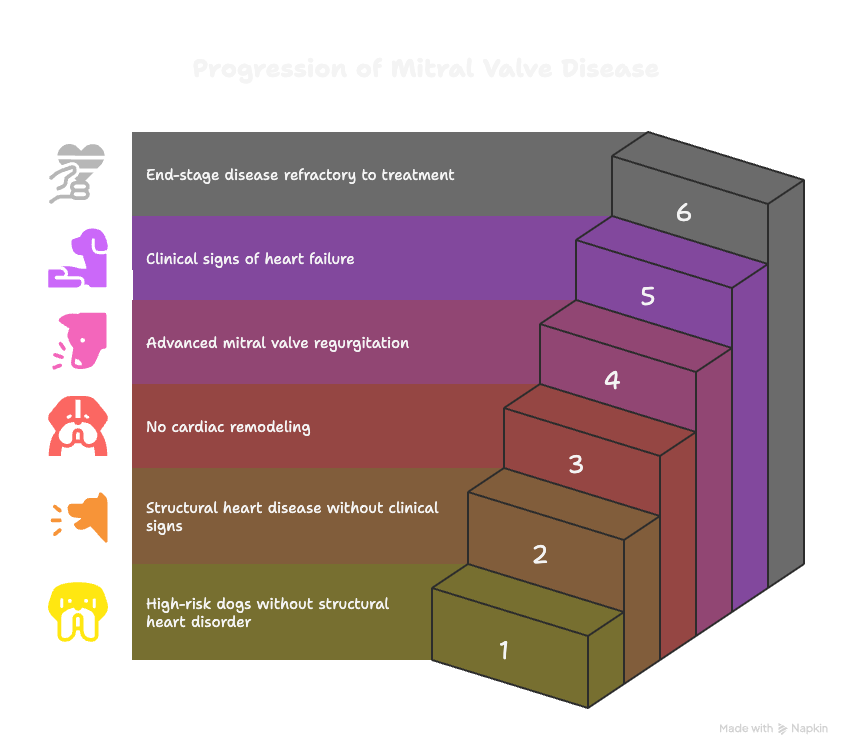

Stages of Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs

Typically, the first sign of mitral degeneration is detected as a low grade heart murmur that increases over time based on many factors including heart muscle strength, age, chord rupture, or other complicating factors. Radiological examinations, echocardiograms, Doppler ultrasounds, electrocardiographic, and blood tests (NT -proBNP and Troponin I) will allow a complete cardiac assessment to be carried out in order to classify the insufficiency in the heart.

Below are the ACVIM guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of mitral valve disease in dogs:

This staging system for MVD in dogs describes 4 basic stages of heart disease and heart failure:

Stage A identifies dogs at high risk for developing heart disease but that currently have no identifiable structural disorder of the heart (eg, every Cavalier King Charles Spaniel or other predisposed breed without a heart murmur).

Stage B identifies dogs with structural heart disease (eg, the typical murmur of mitral valve regurgitation, accompanied by some typical valve pathology, is present), but that have never developed clinical signs caused by heart failure. In a change from the 2009 recommendations, strong evidence now supports initiating treatment to delay the onset of clinical signs of heart failure in a subset of stage B patients with more advanced cardiac morphologic changes.

Stage B1 describes asymptomatic dogs that have no radiographic or echocardiographic evidence of cardiac remodeling in response to their MMVD, as well as those in which remodeling changes are present, but not severe enough to meet current clinical trial criteria that have been used to determine that initiating treatment is warranted.

Stage B2 refers to asymptomatic dogs that have more advanced mitral valve regurgitation that is hemodynamically severe and long-standing enough to have caused radiographic and echocardiographic findings of left atrial and ventricular enlargement that meet clinical trial criteria used to identify dogs that clearly should benefit from initiating pharmacologic treatment to delay the onset of heart failure.

Stage C denotes dogs with either current or past clinical signs of heart failure caused by MMVD. It is important to note that some dogs presented with heart failure for the first time may have severe clinical signs requiring aggressive treatment (eg, with additional afterload reducers or temporary ventilatory assistance) that more typically would be reserved for those patients refractory to standard treatment.

Stage D refers to dogs with end-stage MMVD, in which clinical signs of heart failure are refractory to standard treatment. Such patients require advanced or specialized treatment strategies to remain clinically comfortable with their disease, and at some point, treatment efforts become futile without surgical repair of the valve.

Dogs diagnosed with MMVD require a lifetime of medical follow-up with an update of the medical treatment plan as the disease progresses. Ideally, a tailored treatment and monitoring plan should be made for each dog.

Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs Frequently Asked Questions and Answers

1. How to prevent mitral valve disease in dogs?

While Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease (MMVD) is a degenerative condition—especially common in small-breed dogs like Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, Dachshunds, and Chihuahuas—certain proactive measures can help delay its progression and support long-term heart health. These include:

Routine veterinary checkups with early auscultation to detect heart murmurs before symptoms appear to be the best method of detecting heart disease early and to prolong a dogs life through optimal treatment options if necessary.

Maintaining a healthy body weight to reduce stress on the heart. This includes nutritional and supplemental considerations.

Feeding a balanced, heart-supportive diet, ideally low in sodium and enriched with Omega-3 fatty acids is highly recommended to maintain optimal heart health support.

While MMVD can’t be completely prevented in predisposed breeds, these steps can significantly improve your dog’s quality of life and delay the onset of symptoms.

2. Is mitral valve disease in dogs painful?

MVD in dogs itself is not painful, as the heart’s valves do not contain pain receptors.

However, complications from advanced disease such as difficulty breathing due to congestive heart failure (CHF), coughing, and fatigue can cause distress. Dogs experiencing respiratory distress or syncope (fainting episodes) due to reduced blood flow may appear uncomfortable, lethargic, or anxious.

3. What causes mitral valve disease in dogs?

The most common cause is myxomatous mitral valve degeneration (MMVD), a progressive thickening and deformation of the mitral valve leaflets.

This is a genetic and age-related condition, primarily affecting small- to medium-sized breeds.

Other diseases of the mitral valve are possible, such as congenital malformations or, very rarely, infections of the valve, can also cause regurgitation. Consulting with a board certified cardiologist will help determine the underlying cause.

4. Is mitral valve disease in dogs expensive to treat?

Yes, treatment can become costly over time.

Initial diagnostics such as echocardiograms, chest X-rays, and bloodwork may cost several hundred dollars.

Once Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) develops, lifelong medications (e.g., Pimobendan, diuretics, ACE inhibitors) are necessary, costing $50–200+ per month depending on the dog’s size and severity.

Advanced treatments, like mitral valve repair surgery, are available in some countries and can cost $20,000–$50,000 USD.

5. Can mitral valve disease in dogs be cured or reversed?

No, myxomatous disease is not curable or reversible.

Medical management aims to slow progression, prolong survival, and manage symptoms.

Surgical mitral valve repair, performed by specialized teams (e.g., in Japan, the UK, and select US centers), can correct the leaky valve and potentially extend a dog’s life significantly.

6. How fast does mitral valve regurgitation progress?

Progression varies greatly by individual dogs. Some dogs with a murmur may live for years without symptoms, while others progress to heart enlargement and CHF within months.

Generally, once signs of moderate to severe mitral regurgitation or left atrial enlargement are present, more frequent monitoring (every 3–6 months) is needed to adjust medications and manage progression.

7. How long will a dog live with a heart murmur and mitral valve disease?

Dogs can live for many years with MMVD, especially if diagnosed early and monitored closely.

Stage B1 (murmur but no significant heart enlargement): Dogs may live a normal lifespan.

Stage B2 (heart enlargement without heart failure): Median time to develop CHF is ~3.3 years with appropriate medical management.

Stage C (CHF present): With medications, dogs may live 1–2 years, sometimes longer with proper care and quality of life support.

8. Where is the mitral valve located?

The mitral valve is located between the left atrium and left ventricle of the heart. It plays a critical role in one-way blood flow—allowing oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to pass into the left ventricle while preventing it from flowing backward during each heartbeat.